[Note: if you’re a reader but not a writer, just check out the book and see if you like it—this post is more about the writing process than a real review of the book. If you’re one of the many writers on Substack, this is a book you can learn from and use its techniques. Thanks for reading! ]

Last year I bought a copy of Chelsea Girls, read about 25 pages on a train ride, then got a flurry of ideas for my own work, closed the book, opened the laptop, and started writing. It’s one of the many books I’ve returned to over the years for inspiration, and it’s how I determine which books I keep. After Black Sparrow Press shut down, this book was hard to find for a long time until it was reissued by Ecco.

Again, I find myself writing a personal narrative and turned to one of my secret weapons. My next novel, as I’ve said in previous posts, is a second person, internal narrative. It follows the narrator in four different decades, mostly 1985 and 2015, but also 1995 and 2005. As much as possible, I want the writing to sound like the inside of my head.

My thought process, however, bounces from one memory to another, with distractions when I see the day’s mail or spot a mouse or smell my neighbor smoking weed—it’s in a line, of sorts, it’s linear, technically, but it’s a curly line, like a electric train set built with tracks from 16 different sets. Or maybe you remember Billy Keane’s wanderings in the Family Circus comic strip—like that, but imagine Billy wandering through a neighborhood of horrible regrets, anxieties of the future, and lyrics to pop songs he hasn’t heard in thirty years. So I have to fudge it, somewhat, because there’s no way in hell that my mind will stick to a subject or story for 50,000 words, but I want to get as close as I can.

Enter Chelsea Girls

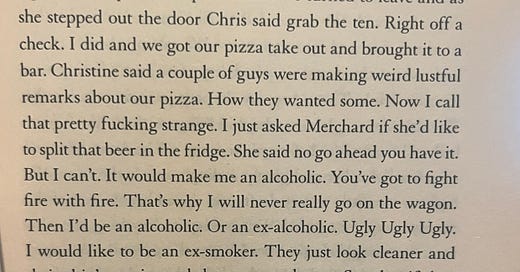

What I really like happens at “I just asked Merchard…”—Eileen stops telling the story and switches to telling the reader what’s happening in the room as the story itself is being written. The writing of the story has become the story, for just two sentences. The writing then pivots again into Eileen’s mind, their theory on smoking and drinking, and whether or not they can quit, or if they even want to.

This unique style removes one layer of pretense found in most creative nonfiction and memoir—the conceit that the author remembers exactly what was said by each person, and the result is writing that more resembles the author’s thought process and true storytelling than most writers’ techniques. What we’re left with is a one-sided conversation between the author and whomever reads the text. The text flows as easy and unbridled as if we were hearing it over the phone. The style mimics someone who has either an attention span issue or is jacked up on mild stimulants—it’s not quite Kerouac’s Benzedrine-fueled The Subterraneans nor is it the cosmic drone of William S. Burroughs, but more of an overcaffeinated confessional.

I’ve met Eileen before, but we don’t know each other for me to say what it is, but if this came from me, just be assured, my thought process is very much like this, caffeine or not.

Diagetic vs Non-Diagetic

Chelsea Girls uses a narrative structure breaks all the rules I would use when teaching someone how to write. There are no breaks between what the narrator says and what another character says and what is being thought by the narrator. Subjects change midsentence, and often the beginning of the paragraph doesn’t match with the end. The voice employs diagetic and non-diagetic dialogue interchangeably with no set system of switching back and forth. It’s a rambling discourse without much visible form. But here’s the magic of it: it works, and I have no idea how.

Before I get too much further, I want to explain “diagetic.” The term is most commonly used in film in relation to the music—is the music in a film heard by the characters or just the audience? Sometimes, the characters of the film can hear it, and this is diagetic music. Non-diagetic music is what the viewers hear. There are some directors, namely Martin Scorsese and Spike Lee, who love to play with this, having music shift between the viewers’ ears and the reality of the world they created. Myles has some lines that are only for the reader, and others are two characters talking to each other, and the switches happen without warning.

Eileen doesn’t use quotation marks when most writers do. Watch what’s going on in the above paragraph when the text says “Chris said grab the ten” and later “She said no go ahead you have it.” Eileen slips in and out of dialogue as needed. From this one excerpt, it might look very confusing, but by this point in the book, either the reader has gotten into the rhythm of this or they have put the book down in utter confusion.

Thought Mapping

This is a term I use to describe how prose that I’m reading influences how I think. If there’s a better (or real) term for this, let me know. Irvine Welsh’s work does this to me—after about ten pages, I’m thinking in a Scottish accent, even for a short while after putting the book down. See also: Mark Twain. Hubert Selby. Sherman Alexie. Charles Bukowski. And when I read Philip K Dick, I become paranoid of absolutely everything in the house.

In Chelsea Girls, after a short time, my thoughts get in sync with Eileen’s prose, and the words have a magical flow. The stories are real, and are entertaining even when they tangent away without resolution. This is a quality I would also use to describe why I didn’t like another book—somehow, Myles gets it just right, and it works.

I love this book. You are brave to take on its mechanics.

I love Irvine Welsh as well. Have you ever read "Maribou Stork Nightmares?" It's my favorite novel of his. I also really like his short stories. He's got a wonderful collection with the best title ever: "If You Liked School, You'll Love Work"

Just in that paragraph I am totally mesmerized by that voice and I know exactly what you mean--if I tried to imitate this I'd fail and in other hands this could be miserable or just kind of lame, but I'm instantly in her head and carried along for the ride, an interior monologue of mind fugue poetry. Great stuff.