Thoughts of Frank Kozik

Frank Kozik died this past weekend. There were posts on all his official social media. I don’t know any more details than that. And I’m not here to describe what his legacy is on poster art or toys or whatever—there are plenty of people already doing that—this Variety article is a good overview. If you scroll through your social media accounts, chances are the artists and bands you follow are each giving a piece of the puzzle to you. As with a lot of my other writing, Frank’s death is a rock thrown into the pond of my mind that creates ripples of thoughts.

To talk about Frank’s work, you have to understand the importance of rock posters in the ‘90s, and that requires understanding of the importance of posters and flyers to the music scene, and that requires understanding of the former impermanence of live music. Do I make this whole piece be a Geriatric-X piece about how we used to find out about shows and if you weren’t there, you missed it, and you would never get a chance to buy that shirt or poster again and there would be no recordings or pictures taken? I definitely could…and I am tempted but I won’t.

I want to talk about my first full-length book, which involves Frank. After all, this Substack is meant to be about me and media that influences me. So yeah, kids, Grampa’s about to take you way back to 1994, when I wore a baseball cap backwards and I thought my Charles Manson T-shirt was transgressively cool. Everyone shared a phone with their roommates and it was attached to the wall…etc.

San Francisco, 1994

After years of chapbooks, zines, and bar room poetry readings, my first book was in the works. It was with Manic D Press, who was transitioning away from chapbooks and a few perfect bound books to just the perfect bounds. This is a spiritual move for a small publisher, a change from being a big small press to a small big press. They had the same distributor as many bigger presses, but 99% of the work was done by Jennifer Joseph. As an author, you had to chip in as much as possible, doing jobs that were out of your hands at other publishers, and in this case, my job was procuring the cover art from Frank Kozik.

I worked upstairs from Man’s Ruin, Frank’s record label, at underground comix publisher Last Gasp. Last Gasp was often visited by local weirdos and icons. I met everyone from Timothy Leary to Robert Crumb up there. But Frank intimidated me. The aforementioned were old enough to be my crazy uncles who liked talking to young’uns but Frank was like a senior and I was a freshman in our scene. He was just enough older and had been around just a little longer and was one of the big names. He did all the posters and album cover art for bands like The Melvins (side note: this is being written under the influence of Houdini, their Kozik-arted album from 1993, a seriously underperforming album of the time, if a gold record can be considered such).

Jennifer basically told me to suck it up and ask him for cover art. The worst case would be that he said no. I put it off as long as possible. This was not something I could ask the other guys in his office, Mike Lavella and Nick Rubenstein, to do for me. They were good friends of mine. They were all for me, but this ask had to come directly from me.

On my way back from lunch, I saw Frank outside smoking. He looked pissed off, and he probably was. But who knows? Frank had resting angry-biker face.

Did you ever see the Brady Bunch episode when Peter’s voice changes? That is how I remember all my dialogue with him. That day.

“Hey Frank,” I squeaked.

“Hey.”

“I have a book coming out, and I need art for the cover. I wanted to ask if you know, I could get some of yours.”

“What kind of book is it?”

“Poems,” I said, never feeling worse about writing poems. I would have felt tougher saying it’s a zine of enema reviews. “And some stories.” Not better.

“Yeah. Sure.”

WHAT! HE SAID YES. DON’T FREAK OUT IN FRONT OF HIM. FOR THE LOVE OF ODIN, DO NOT HUG HIM. ACT LIKE A HUMAN AND PLAY IT COOL.

“Cool, how do we do this?”

“I don’t know. I’m busy. Tell your publisher to call me.”

And with that, he went back inside. I was flop-sweat damp.

King of the Roadkills (1995)

I thought the book would fix me. I thought it would get me the respect and viability to become a part of the Hollywood machine, to blend into the overlap of literati and filmmakers, in the way Hunter S. Thompson was doing appearances with John Cusack and Johnny Depp at the Viper Room, how people like Sean Penn would occasionally just sign up at open mike poetry readings, and The Largo had a reading series booked by the casting director of Spinal Tap. I thought it would get me the literary respect to go to universities and talk about my process, and that I could go to the racetrack with Bukowski— “You got it, kid!” he’d say to me. Most importantly, I thought it would give me the social value to be invited to parties and weddings, and it would make up for whatever I was missing inside so that someone would love me. I was emotionally broken, with two untreated psychiatric conditions for which I was self-medicating, and the missing part of my life was this book.

But it was just a book. And even then, most people don’t give a fuck about your book, and good god, do they not want to hear you read a poem from it. Far from fixing anything in your life, it will create new problems you’re not used to dealing with. There were older writers who thought I “jumped the line.” There were many more writers rejected by the press who took out their frustrations on me. My expectations of how being a published author would change my life were unrealistic.

But fuck the world, I had the coolest-looking poetry book ever made. No matter what people thought about it, regardless of the sales, my book looked better than any other on the shelf. I had a Kozik cover.

Last Gasp, 2001–2007

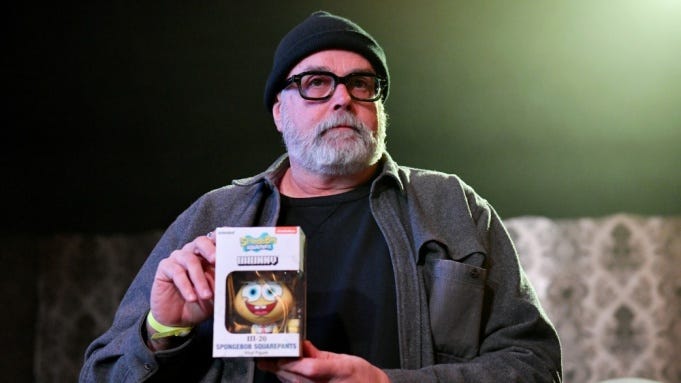

I ended up back at Last Gasp some years later, and we published some books with Frank. Man’s Ruin was long gone, and he had resurfaced in the world of collectible toys and was done with the rock poster scene. We talked business quite a bit at that time, and once I got into the rhythm of his forthrightness, he was incredibly easy to deal with, such as 90 second to-the-point phone calls that took 30 minutes with anyone else. After I left Last Gasp in 2007, I never ran into him again.

My lasting memory of Frank is of him on a motorcycle he loved. It was a deadstock BMW bike from the ‘40s that had never been taken out of the crate and assembled. Basically, a brand new 50-year-old bike. He just looked right on that thing, bluttering around the Mission District streets. Now, seven years removed from San Francisco, this is how I picture everyone from there, in their finest moment. RIP Frank!