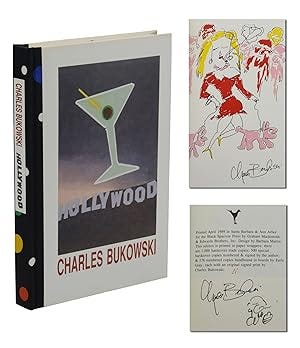

It was my birthday recently and a book came in the mail. I’m a lot of people’s token author friend, and it’s not unusual for someone to give me a book. Often, there’s a note that I enjoy more than the book, that says something like “this was way too weird for me—I think it’s right up your alley.” The note on this one said that they found it in Silver City, New Mexico, and they knew I was a big fan. This book was Charles Bukowski’s Hollywood, and most importantly, it’s a Black Sparrow Press edition.

Black Sparrow Press is close to my heart, the same way a lot of my generation is partial to a record label. I was deep in several music scenes of the Bay Area1, but my real passion was for poets and subculture writers. There were presses I followed, others to whom I submitted, and I was always on lookout for new ones. There were two big ones I really admired: City Lights and Black Sparrow, for the same reason: they were home to Charles Bukowski.

Bukowski was my doorway into the world of subcultural literature. Right now a lot of you are rolling your eyes at this post, and the rest of you are wondering why you’ve never heard of this guy, and there are good reasons for both of these reactions. But I want to scoot past Bukowski’s stigma2 if I may and get into his primary publisher.

Black Sparrow Press was founded by John Martin, who was an avid book collector and a big Bukowski fan. Back then, Bukowski had only been publishing steadily for a handful of years, in small literary mags and by the artsy LouJon Press in New Orleans, whose books were only known to the collectors, and more so as pieces of art than books to be read. These editions are super rare and very expensive. John had a vision of bringing Bukowski’s writing to the masses, so much so that he started his own press in 1966.

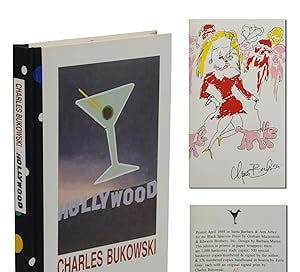

The books are catnip to literary collectors. They’re gorgeous. As far as I know, they were all designed by Barbara Martin and Graham Mackintosh. You won’t find a price or a bar code on any of them—they didn’t like the way it looked. The paper, even on the cover, is soft and the editions have a nice weight in your hands and they catch the light fantastically—I don’t know if this is a problem for anyone else, but many books use a paper stock that is too white, if that makes any sense—just pick up a Black Sparrow title and I think you’ll get it. They’re cool, and they’re all quickly identifiable.

But the same attributes I like, all the bookstores hated: no bar codes, no prices, and the cover stock is so soft that the books will quickly become too shelfworn to be sold. And there was another huge problem with Bukowski books: they were consistently a top shoplifting target countrywide. There were a lot of distributors who didn’t want to carry them without a bar code and a price, and a lot of retailers who didn’t want to carry books that they had to buy but were always stolen. The City Lights Bookstore kept them behind the counter to keep them from disappearing immediately.

I know it sounds like Grampa Hipster stories to tell you that it used to be hard to find books, like you couldn’t get a certain title in many cities, that you had to visit somewhere cool to find a copy of The Anarchist Cookbook or the Henry Rollins books. I can’t tell you how spiritually exciting it was to work at Last Gasp, which turned out to be a source for such weirdo literature in all the nooks and crannies of the United States. In the ‘90s, if you went to a skateboard shop in Tennessee or a headshop in Lawrence, Kansas and bought some cool books, chances are it was myself or one of my coworkers who sold those books to that store further up the source of the subculture river. But let’s get back to the point of the post: Black Sparrow.

John Martin published Bukowski’s poems during his tenure at the post office, and also reprinted the impossible-to-find short-run earlier work. In my opinion, Bukowski’s run from 1960 to 1972 is the best body of work published by any American poet—you won’t be able to convince me otherwise. There are some good poems after that, but this is the era of the cover-to-cover bangers. This is the metric by which I judge his work and still consider him my favorite.

But the real contribution that John Martin made is when he told Bukowski to quit the post office and just write. The agreement is that Martin would send the frugal writer a monthly allowance as an advance against future book sales. I can’t tell you what a bad idea this was for an author who had just published poetry. Martin’s stipulation was that Buk would have to write prose, which he hadn’t done in book form. This birthed Post Office a few weeks later. Yes, weeks. The legend is the manuscript came back in three weeks. Bukowski NaNoWriMo’d3 his first book and turned it in.

Martin talks about how the agreement almost ruined him when the Europeans latched on to his work just in time. Bukowski was born in Germany in 1920 to a German mother, and thus, the Germans considered him one of their own. He quickly rose as a cool American brand, like Marlboro cigarettes, Harley Davidson motorcycles, and Levi’s jeans. Bukwoski’s books started selling. A lot. The man was an odd celebrity in Europe, and his legend was growing in the United States.

John Martin took this money and published a lot of other people. As a young, curious, literary brat, I scanned poetry shelves for the distinctive spines and read at least one poem out of everything I found. This is how I came upon Mad Dog, Black Lady by Wanda Coleman and Chelsea Girls by Eileen Myles. There were two books by Nancy Boutlier as well. And while my timeline for this is at the very least confusing, I just want to say the best thing they did was publish the works of the out-of-print John Fante, who is an American treasure and one of the best writers from Los Angeles.

At some point (and it may be in the book Women) Bukowski said that his favorite writer was John Fante, whose books he read during his alcoholic years while killing time at the LA Public Library. Immediately, every Bukhead4 went looking for Fante’s work. It was long out of print. His publishers had gone out of business in the Depression. So John Martin decided to bring those old books into print. But first they had to find John Fante or his heirs.

They found Fante, a blind, double amputee dying in a hospital, and told him “Mr. Fante, we want to reprint your works.” Not only did John Fante live for many years after that, he dictated more books to his wife who typed them up. Mind you, Fante had a reputation as an angry alcoholic, so this couldn’t have been pleasant. These books are great, but his wife, Joyce is the real hero of the story. I can’t imagine doing this. I would have left a recording of someone typing playing and left the room.

The point is, and I do have one, that John Martin started his press because he loved books and wanted everyone else to love them. And once everyone did love them, he continued to find other relatively unknown writers and broke their careers as well. So even if you think Bukowski’s a pig or whatever, and I’m not saying he’s not one, the money that the books brought in printed a lot of other books I’m sure you’ll like.

Hollywood is a fun book. It’s a behind-the-scenes look at the making of the movie Barfly, which was as close to mainstream success as Bukowski got. Unfortunately for me, it was also when he got successful enough that he could turn down readings so I never got to see him live. I’m going to give it a re-read, but I wanted to write all this because of the edition of this book.

John Martin eventually retired from the book business, and sold off the big titles to Ecco, an imprint of Harper Collins. The rest of the titles went to a small publisher, David Godine, who has continued printing under the Black Sparrow name, but whose books I rarely see around. Harper Collins kept a lot of the book design, but changed the paper stock and put the bar codes and prices on. These books are a lot easier to find now, but they look weird. The new editions looked like photocopied editions of the old books, and then they all got new covers that didn’t sell me either. But it made me treasure these old copies so much more, and remind me of a more magical time in my reading life, when every week I found my new favorite book.

[Some last notes here: I didn’t bother looking much up. Most of this knowledge comes from years of being around book nerds, reading articles, and watching documentaries. But it’s meant to be enjoyed as my personal history, not as an historical document.]

There were two punk scenes in the Bay, and a lot of people didn’t know each other. Some bands were popular in San Francisco and not in the East Bay, and vice versa. It was weird. I also worked at a bar that had what I will just call “college radio” music and leave it at that.

I’m a Bukowski fan, an atheist, I follow the St. Louis Cardinals baseball team, and I’m an avid Steph Curry follower. I write poetry. These things are all true, and I don’t usually talk about them in public because of the social stigma they carry.

NaNoWriMo is a thing where people try to write a draft of a novel in one month.

Not really a term anyone uses.

Nice one, Bucky, and great info about Fante's twilight years. I once did an SF Weekly column about book shoplifting, and called a number of bookstores to ask the most-stolen author, which was Bukowski, hands down across the board, as you write here. I then called Black Sparrow Press in Santa Rosa to ask John what Bukowski might think of this, and he replied that Buk would have HATED to learn that.

bukhead = bukowski stan; buckhead = bucky stan